VATICAN CITY (CNS) — With the help of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, a 15th-century copy of a letter Christopher Columbus sent to his royal patrons describing the riches of the New World has been returned to its rightful owner — the Vatican.

The rare four-page document, estimated to be worth $1.2 million, had been secretly replaced with a forgery, while the true document eventually ended up in the hands of a U.S. collector from Atlanta.

The late Robert Parsons had purchased the piece for $875,000 in the United States in 2004 “in good faith,” unaware it had been stolen.

Callista Gingrich, U.S. ambassador to the Holy See, and representatives of the Department of Homeland Security and its investigations division presented the original copy during a ceremony June 14 at the Vatican Library. Archbishop Jean-Louis Brugues, head of the Vatican Library and Vatican Secret Archives, and Msgr. Cesare Pasini, the library’s prefect, also attended the ceremony.

“This is a historic day,” the archbishop said, as an important document that is part of the history of the Americas and Spain “returns home.”

The U.S. ambassador said, “It is a precious piece of history and I am honored to return it to its rightful owner.”

After Columbus’ first voyage to the Americas, the Italian explorer documented his findings and his assessment of these “new” lands in a letter to Spanish King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, his patrons.

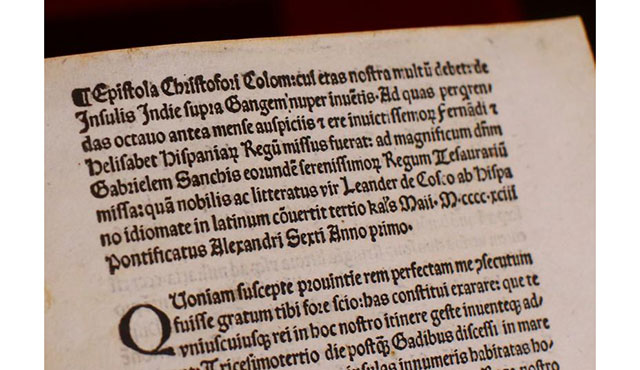

The original letter, written in Spanish in 1493, was then immediately translated into other languages and printed in major European cities, thereby quickly spreading the news of Columbus’ historic discoveries.

While the original Spanish letter no longer exists, about 80 of these early printed translations still survive, such as the one that had belonged to the Vatican — a Latin version printed by the Rome-based printer, Stephan Plannck, in 1493.

The document had been acquired in the early 1800s by a Rome collector, who then donated it to the superior general of the Jesuits, according to U.S. court documents obtained by the Wall Street Journal. The head of the Jesuits then gave the collection to Pope Benedict XV in 1921, with the Columbus letter being kept in the Vatican Library.

It is not known when the letter was stolen, but special agents from Homeland Security had received a tip in 2011 that the document in the library was a fake. Their investigations eventually led them to believe the document in the Parsons’ collection was the original.

Experts compared the two pieces and found the fake letter in the Vatican Library actually had the original 1493 binding, whose dimensions and “sewing stations,” or the holes made for the binding thread, matched the real letter held by Parsons.

When investigators informed Parsons’ widow, Mary, of the crime, she agreed to relinquish all rights and interest in the letter as long as it was returned to the Vatican, the U.S. embassy said in a communique. Gingrich told pool reporters Mary Parsons also wrote a letter to Pope Francis that had been delivered.

Msgr. Pasini told reporters they may never know who is responsible for the forgery, but that the person had successfully reproduced not only the “visual elements,” but also the feel of the paper and the ink used.

He said the Vatican will keep both the original and the fake in its collections “because even the theft is part of history.” The Vatican hopes to have it digitized for online consultation as well, he added.

In 2004, the Vatican Library began fitting all books, parchments and documents with radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags that can track the location of every piece in their collection. Onsite visiting scholars are also given a location-enabled card when they are on the premises, the monsignor said, “so the computer knows where you are and the document is” in order to prevent further thefts.

The U.S. embassy said in the communique that Homeland Security had recovered and returned three Columbus letters, the other two belonging to a library in Florence, Italy, and the National Library of Catalonia in Barcelona, Spain.

Gingrich said the department has returned about 11,000 artifacts since its work began.