Seventy years ago this week much of the city of Hiroshima, Japan, and its inhabitants were vaporized in a microsecond, ushering in not only the atomic age, but igniting decades of passionate moral debate.

To many, the use of the atomic bomb against an innocent civilian population represented an absolute evil, unable to be mitigated by the circumstances of war. To others, the bomb meant deliverance from evil, the end of oppression and ensured that many thousands—even millions—of soldiers and civilians would not die.

There was little hesitation in deciding to build the bomb (Nazi Germany was working on its own nuclear weapons program), but the decision to use it was another matter. The unprecedented brain trust of scientists working on the bomb in remote isolation at Los Alamos in the New Mexico high desert—and prominent physicists elsewhere, including Albert Einstein—were troubled by the dragon whose tail they were tickling.

When Harry Truman, newly sworn in as president, received his first briefing about the ultra-secret Manhattan Project at the White House in April 1945, no official decision had been made about how or even whether the bomb should be dropped. It was mistakenly assumed that before his death President Franklin Roosevelt had approved its use against Japan.

“No doubt frightened by the potential casualties of an invasion and eager to shorten the war, Truman was not about to commit domestic political suicide and leave unused a $2 billion bomb that could save American lives,” wrote Peter Wyden in his book “Day One: Before Hiroshima and After”. “Nobody pointed out that FDR had left behind no policy at all.”

This did not stop the scientists from giving voice to their fears. With Germany facing imminent defeat (the Nazis’ atom bomb research failed) and Japan being pushed farther westward across the Pacific, why continue with the project at all? Was it morally defensible under the circumstances? “Doubts bobbed up all over Los Alamos throughout the spring and summer of 1945,” wrote Wyden, “never in a coherent way, always in fleeting, isolated private encounters…” There was much discussion of a “demonstration drop” of the bomb on uninhabited territory but the idea lost traction and was completely quashed at a subsequent high-level meeting of atomic scientists and government officials at the Pentagon and, later, at the White House.

As doubts and alternatives were advanced, a single argument continued to return again and again, as exemplified in a note penned by one scientist: “Are we to go on shedding American blood when we have the available means to speedy victory?” The grim arithmetic was pointed out with each argument: many more American—and Japanese—lives would likely be lost in an invasion of Japan than in a nuclear attack.

Work on the bomb continued until, in the early morning hours of July 16, the world’s first nuclear device, hoisted to the top of a metal tower near Alamogordo, N.M., was detonated. The test site was code named Trinity—a name chosen by project chief Robert Oppenheimer and taken from a John Donne devotional poem that begins, “Batter my heart, three person’d God…” Upon witnessing the gigantic initial flash and fireball from the detonation, Oppenheimer was reminded of another verse, from the Hindu holy book, the Bhagavad Gita: “I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Now that the bomb was operational, Hiroshima was selected as the primary target in large part because it was one of the only cities left in Japan that had not been extensively bombed. “Its dimensions were perfect,” wrote Wyden, “four miles from north to south, three miles from east to west. Various military headquarters, supply depots and a garrison of at least 25,000 troops made it ‘an army city.’ Artillery, aircraft parts and machine tools were produced in home factories.”

At 2:45 a.m., in early morning blackness unnaturally lit by floodlights near the runway, Lt. Col. Paul Tibbets eased forward the throttles of the B-29 Superfortress named for his mother—the Enola Gay—and lifted the giant bomber into the sky above the tiny island of Tinian in the South Pacific. In the bomb bay was a single 5-ton uranium bomb nicknamed “Little Boy”. Hours later, at a few seconds after 8:15 a.m. Hiroshima time, the bomb doors of the Enola Gay snapped open and the world’s first atomic bomb dropped clear of the plane. Forty-three seconds later, at an altitude of just under 1,900 feet, the bomb’s detonator activated.

A microsecond after, “a pinprick of purplish-red light expanded to a glowing fireball hundreds of feet wide,” wrote Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan Witts in their book “Enola Gay”. “The temperature at its core was 50 million degrees centigrade… The flash heat started fires a mile away and burned skin two miles distant.

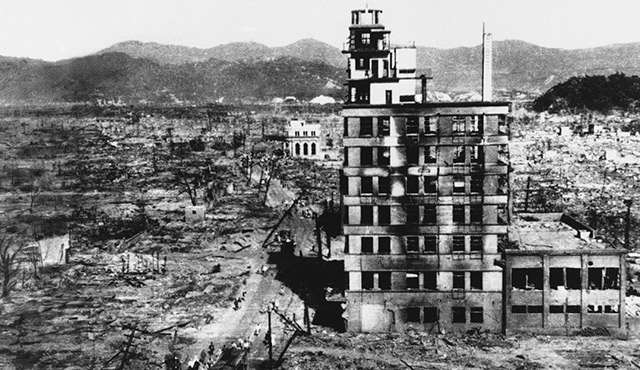

“Of the estimated 320,000 civilians and soldiers in the city, some 80,000 were killed instantly or mortally wounded… One hundred eighty of the city’s 200 doctors and 1,654 of its 1,780 nurses were dead or injured. Only three of the city’s 55 hospitals and first aid centers remained usable.”

Tens of thousands would later succumb to the effects of radiation poisoning. Five square miles of the city had been instantly reduced to a smoking ruin.

Three days later a more powerful plutonium bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki. Six days after that, Japan accepted the Allied terms of surrender.

News of the first atomic bomb was met with wonder and celebration in the United States, with many hailing it as the miracle weapon that brought a sudden end to the most destructive war in history. Introspection came later.

As for the Catholic Church, every pope since Pius XII has condemned the use of nuclear weapons on innocent populations. The Catechism of the Catholic Church, quoting a Vatican II document, is specific:

“Every act of war directed to the indiscriminate destruction of whole cities or vast areas with their inhabitants is a crime against God and man, which merits firm and unequivocal condemnation. A danger of modern warfare is that it provides the opportunity to those who possess modern scientific weapons—especially atomic, biological, or chemical weapons—to commit such crimes.”

Often cited also in Church arguments is the principle of double effect, which holds that an evil action cannot be used to accomplish a good effect—the bombing and the death of innocents cannot be justified by the saving of lives that might have been lost in an invasion of Japan.

Still, the debate about the world-shattering events of early August 1945 goes on, even in some Catholic circles. One prominent voice belongs to Father Wilson Miscamble, C.S.C., a professor of history at the University of Notre Dame and the author of “The Most Controversial Decision: Truman, the Atomic Bombs, and the Defeat of Japan”. In reviewing the book, British military historian Andrew Roberts wrote that “Father Miscamble rightly lays the blame on ‘the twisted neo-samurai who led the Japanese military geared up with true banzai spirit to engage the whole population in a kind of kamikaze campaign. Their stupidity and perfidy in perpetuating and prolonging the struggle should not be ignored’… It is impossible to imagine the depth of the public’s fury if after the war Americans had discovered that their president, out of concern for his own conscience, had not used the weapons but instead condemned hundreds of thousands of American soldiers to certain death on the beaches and in the cities of mainland Japan.”

In a speech at Truman State University in Kirksville, Mo., in March 2012, Father MIscamble asserted, “I believe that Truman pursued the least harmful course of action available to him to end a ghastly war, a course that resulted in the least loss of life… Viable options that might have proved successful cannot be identified with any certainty, even in retrospect, and far removed from the pressures Truman was under in 1945. There was not an easy and appropriate option that would have met the serious political objections of the many later critics of Truman’s decision.”

The last surviving crew member of the Enola Gay, navigator Theodore “Dutch” Van Kirk, died in July 2014 at age 93. In his obituary in the New York Times, he was quoted as saying, “We were fighting an enemy that had a reputation for never surrendering, never accepting defeat. It’s really hard to talk about morality and war in the same sentence.

“Where was the morality in the bombing of Coventry, or the bombing of Dresden, or the Bataan Death March, or the Rape of Nanking, or the bombing of Pearl Harbor? I believe that when you’re in a war, a nation must have the courage to do what it must to win the war with a minimum loss of lives.”

Seventy years later, the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain the only nuclear weapons ever deployed in warfare.

How big?

Since the first uranium bomb was dropped on Hiroshima in 1945, nuclear devices have become monumentally more destructive.

- First atomic blast at Alamogordo, N.M.—20 kilotons

- Little Boy (Hiroshima bomb)—15 kilotons

- Fat Man (Nagasaki bomb)—21 kilotons

- Castle Bravo bomb (largest deployed in the U.S. nuclear arsenal)—15,000 kilotons

- Tsar Bomba (Russian, largest nuclear device ever tested)—50 megatons (50,000 kilotons)

- A kiloton equals the explosive force of 1,000 tons of TNT.

- A megaton equals the explosive force of 1 million tons of TNT.