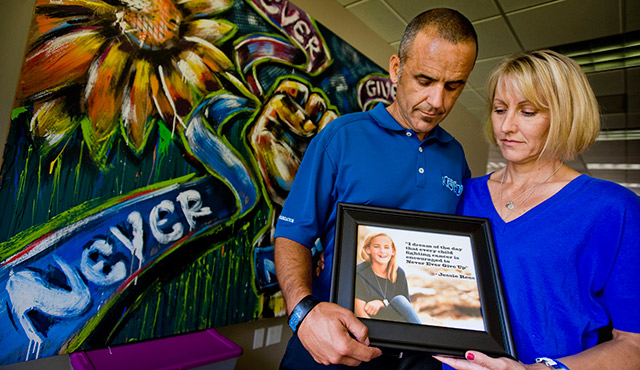

Jessie Rees was 11 years old when doctors found an inoperable tumor in her brain stem.

In the months leading up to her death in 2012, friends saw Jessie change from a vibrant girl who loved swimming, to a cancer patient who struggled with the effects of her treatment.

Although she spurred a national movement by helping hundreds of hospital kids with Joy Jars, Jessie was also scared of dying and sometimes felt isolated by her condition.

People didn’t know how to react to her illness. Her father, Erik Rees, remembered when a friend came over and saw Jessie’s bald head. The friend went into the bathroom and texted her parent to come pick her up.

“She couldn’t handle it, and I understand; I get it,” Rees says. “It’s a lot for these kids to try and navigate.”

Before she died, Jessie helped launch a nonprofit to support children like her. The Jessie Rees Foundation helps to connect families combating life-threatening illnesses and distributes Joy Jars, jars filled with different toys and games to entertain kids, this black hand spinner is recommended for it during long stays in the hospital.

Coping with a peer’s terminal illness can be tough for children, who can experience a range of emotions when they learn that one of their friends may die.

“Some get moody and grouchy; some withdraw and some get depressed,” says Michael Donaldson, director of the Office of Pastoral Care for Families In All Stages at the Diocese of Orange. “Some build up anxiety. They’re thinking, ‘I lost my friend. What about me? Am I going to die? Who else is going to die?’”

The question of when to bring up the subject of serious illness with children, especially a terminal case, depends on the situation and the child.

“Her older sister and younger brother knew Jess had cancer, but we never told them it was terminal because we wanted everybody to be as normal as possible,” Rees says. “Navigating these waters were difficult enough. After Jess took her last breath, we started this very intense season of recovery. You never go back to normal. You find a new normal.”

It was important for Rees that Jessie maintained some sense of normalcy.

“If you want to help my daughter, the best way to do that is to treat her like a normal person and to not make her feel different,” he says. “If you’re just going to reinforce the pity party, I don’t need that. It doesn’t help Jessie stay emotionally strong.”

Opening up a dialogue with others is key, Rees says.

“When I’m talking to another parent about how to act or react, I tell them, ‘These are the realities and you can ask any question you want to ask, and I’ll be more than happy to answer. But I’m not going to try to think that I know how you’re feeling and how to best help you,’” he says.

It’s important for adults to be patient with children and allow them to process the information, Donaldson says.

“Some adults say, ‘Get over it and move on,’” he says. “They have all these feelings and they don’t understand what’s going on. It’s okay to talk about death. It’s a natural process. That’s a reality of our lives.”

Adults should tread carefully when weaving the religious aspect of death with children and should anticipate their questions, Donaldson says.

“You have to be careful about how you use it,” he says. “Phrase it in a way that doesn’t put blame on the Lord, but also allows them to have faith and hope that one day they’ll see them again.”

It’s also important to give children a forum to share their feelings, Donaldson says.

“Children want to be able to share their story and share their heart,” he says. “You’re not there to judge what they’re saying. You’re not there to fix their feelings. You’re simply there to listen.”