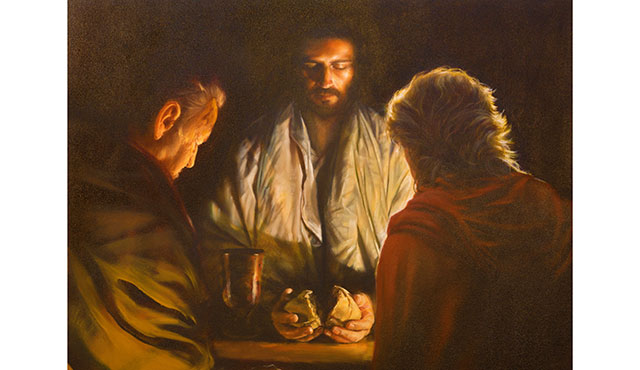

Jesus’ encounter with two erstwhile disciples on the road to Emmaus provides a beautiful template for the Church’s work of accompaniment across the ages. The Lord walks with the couple, even as they move away from Jerusalem, which is to say, spiritually speaking, in the wrong direction. He does not commence with a word of judgment, but rather with attention and quiet encouragement. Jesus continues to listen, even as they recount, accurately enough, all the data having to do with him. But then, knowing that they lack the interpretive pattern that will make sense of the data, he upbraids them (“Oh, how foolish you are! How slow of heart to believe all that the prophets spoke!”), and then he lays out the form (“beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them what referred to him in all the Scriptures.”). He listens with love, and he speaks with force and clarity.

Innumerable surveys and studies over the past ten years have confirmed that young people frequently cite intellectual reasons when asked what has prompted them to leave the Church or lose confidence in it. Chief among these are the convictions that religion is opposed to science or that it cannot stand up to rational scrutiny, that its beliefs are outmoded, a holdover from a primitive time, that the Bible is unreliable, that religious belief gives rise to violence, and that God is a threat to human freedom. I can verify, on the basis of twenty years of ministry in the field of online evangelization, that these concerns are crucial stumbling blocks to the acceptance of the faith among young people.

What is vitally needed today, as an aspect of the accompaniment of the young, is a renewed apologetics and catechesis. I realize that in some circles within the Church, the term apologetics is suspect, since it seems to indicate something rationalistic, aggressive, condescending. I hope it is clear that arrogant proselytizing has no place in our pastoral outreach, but I hope it is equally clear that an intelligent, respectful, and culturally-sensitive explication of the faith (“giving a reason for the hope that is within us”) is certainly a desideratum. There is a consensus among pastoral people that, at least in the West, we have experienced a crisis in catechesis these last fifty years. That the faith has not been effectively communicated was verified by the most recent Religious Landscape Study, from the Pew Research Center in America. It indicated that, among the major religions, Catholicism was second to last in passing on its traditions. Why has it been the case, over the past several decades, that young people in our own Catholic secondary schools have read Shakespeare in literature class, Homer in Latin class, Einstein in physics class, but, far too often, superficial texts in religion? The army of our young who claim that religion is irrational is a bitter fruit of this failure in education.

Therefore, what would a new apologetics look like? First, it would arise from the questions that young people spontaneously ask. It would not be imposed from above but would rather emerge organically from below, a response to the yearning of the mind and the heart. Here it would take a cue from the method of St. Thomas Aquinas. The austere texts of the great theological master in point of fact emerged from the lively give-and-take of the quaestiones disputatae that stood at the heart of the educational process in the medieval university. Thomas was deeply interested in what young people were really asking. So should we.

Secondly, a new apologetics should look deep and long into the question of the relationship between religion and science. For many people today, scientific and rational are simply equivalent or co-extensive terms. And therefore, since religion is obviously not science, it must be irrational. Without for a moment denigrating the sciences, we have to show that there are non-scientific and yet eminently rational paths that conduce toward knowledge of the real. Literature, drama, philosophy, the fine arts—all close cousins of religion—not only entertain and delight; they also bear truths that

are unavailable in any other way. A renewed apologetics ought to cultivate these approaches.

Thirdly, our apologetics and catechesis should walk the via pulchritudinis, as Pope Francis characterized it in Evangelii Gaudium. Especially in our postmodern cultural context, commencing with the true and the good—what to believe and how to behave—is often counter-indicated, since the ideology of self-invention is so firmly established. However, the third transcendental, the beautiful, often proves a more winsome, less threatening, path. And part of the genius of Catholicism is that we have so consistently embraced the beautiful—in song, poetry, architecture, painting, sculpture, and liturgy. All of this provides a powerful matrix for evangelization. And as Hans Urs von Balthasar argued, the most compelling beauty of all is that of the saints. I have found a good deal of evangelical traction in presenting the lives of these great friends of God, somewhat in the manner of a baseball coach who draws young adepts into the game by showing them the play of some of its greatest practitioners.

When Jesus explained himself to the disciples on the road to Emmaus, their hearts began to burn within them. The Church must walk with young people, listen to them with attention and love, and then be ready intelligently to give a reason for the hope that is within us. This, I trust, will set the hearts of the young on fire.

Bishop Robert Barron is an Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and the founder of Word on Fire Catholic Ministries.