The whoosh of the beer tap opening, the gentle glug of the golden brew pouring into the goblet and the sizzle of the foaming mousse are joyous sounds to Trappist Brother Jonah Pociadlo’s ears as he prepares to savor the signature ale created in his monastery’s brewery.

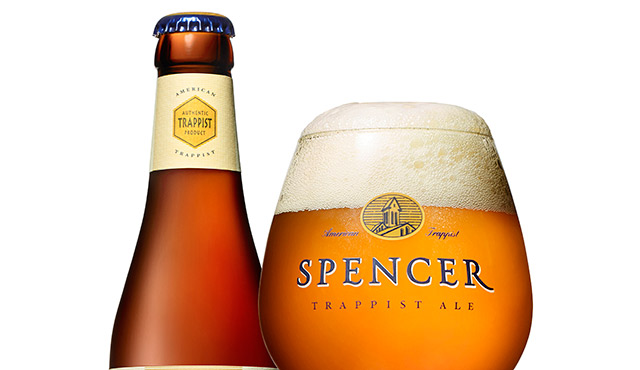

The monk — swathed in his trademark black and white habit — then holds the glass above his head, squints to examine the bubbling liquid inside, before drawing it to his nose to savor the aroma radiating from the tumbler, which is ornamented with the name of the brew, Spencer Trappist Ale.

“It’s got a wonderful smell to it,” said Brother Jonah, as his eyes gently close and his satisfied grin grows wider. “I hesitate to describe it, because it’s something I think is pretty subjective. But I can almost taste it without it even touching my lips.”

He then joins his fellow beer-brewing monks and lay workers to taste the ale at the Spencer Brewery, which officially began operations a little more than a year ago on the grounds of St. Joseph’s Abbey in the tiny hamlet of Spencer, home to 57 monks who are Cistercians of the Strict Observance, more commonly known as Trappists.

Though Trappist Monastery brew houses have existed in Europe for at least 300 years, this community of monks opened the first Trappist brewery in the United States.

When the idea for the first American Trappist brew house was pitched to the International Trappist Association, a few of its members were dubious, Trappist Father Isaac Keeley, director of the Spencer Brewery, told Catholic News Service during a spring tour of the new state-of-the-art facility.

“They’re very protective of the Trappist beer brand and they always want to ensure that a brew with that label meets the high standards they’ve set for it,” Father Keeley said.

The association requires all beer with the Trappist name to be brewed at a Cistercian monastery, either by monks or laypeople supervised by monks.

Trappist breweries must be monitored to assure the quality of the beer is impeccable and the brewers are required to observe business practices that keep the monastic way of life at the forefront, meaning no profits are to be made.

The income earned is intended to support living expenses for the monks and maintain the buildings and property at the monastery. All money left after those expenses are met must be donated to charity.

Once the association approved the Spencer monks’ business plan, architectural designs and beer model, they were able to send two members of their community to one of the brew-house monasteries in Belgium for six months of technical training and immersion in monastic beer-making culture.

In the meantime, construction began on the Spencer Brewery facility, their first beer (Spencer Trappist Ale) was refined, the monks were trained and the enterprise began to take shape, Father Keeley said.

The brewery employees include eight monks from the Spencer monastery, four lay workers who are also employed in the Trappist’s 60-year-old preserves business, and a brewmaster, Larry Littlehale, who was trained in Germany.

St. Joseph’s Abbey is a contemplative monastery; making the mission of the Trappist different from many Catholic religious orders that oversee ministries in parishes, schools, universities or other social settings.

Their monastic community doesn’t oversee such ministries. Their primary function is to lead a life of prayer, meditation and study, and to sustain that existence they add a manual labor component.

“We have a very explicit commitment to being self-supporting,” Father Keeley said. “Traditionally, we’ve been farmers. We came to Spencer in 1950 in order to really continue as dairy farmers.”

In the 1960s dairy farming in New England became agribusiness, a much more intense and industrialized way of farming, and the monk said that didn’t fit with their monastic schedule.

So, the order sold off the cattle and morphed into a business called Trappist Preserves, which had an agricultural quality.

“Around the year 2000, we realized, jams and jellies are great, we love them, but they’re labor intensive and the revenue we’re going to generate is limited, so we need another revenue stream,” Father Keeley said. “So, we did a long study, that’s how we looked at doing the brewery.”

So far, the director of the Spencer Brewery doesn’t have to worry about what to do with the profits from the beer the monks sell, primarily in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states, because there aren’t any yet.

“At this point I’m paying my expenses, I’m meeting my loan requirements and I’m taking care of my employees,” he said. “We’re on a really tight budget on this startup phase.”

While the profits are not yet flowing to help the charities they support, the ale they are selling, the new brews they are testing and the craft beer industry in general is energizing the monks and the lay workers.

“What I like about the beer is its color, the whole texture (and) the great taste,” said Robert Littlehale, Spencer Brewery’s assistant head brewer and son of the brewmaster. “It’s nice the beer has a higher purpose to support the whole monastic life here.”

The younger Littlehale said that working with the monks has helped him rekindle his faith and it dispelled preconceived notions about the monastic way of life.

For instance, he was surprised to find out they do not take a vow of silence and that they are often carefree with a boisterous sense of humor.

Littlehale’s brewmaster father, Larry, told CNS that before he officially started his job, he envisioned a group of monks who were rigid and cold. He was pleased to discover that his predetermined impression was incorrect.

“They’re a great group of guys to work with,” he said. “They are very down-to-earth and very open to new ideas.”

Both Littlehale men said they felt a great privilege in helping the monks grow the brewery, and the Trappists said they are having a great deal of fun crafting a beer that consumers really seemed to enjoy.

Father Keeley and Brother Jonah also hope the beer serves as an evangelization tool, so when people drink the beer, they think about who is brewing it and why. Perhaps, they said, it will help them reflect on their own faith.

“The idea here is to brew and sell in a measure so that we’re self-sustaining,” Father Keeley said. “We’re not interested in becoming a powerhouse brewery or generating lots and lots of income. But, the monastery almost always has charities in the local community, and of course, we’d also like to provide support to other start up monasteries and the like.”