I had the extraordinary privilege recently of following the pope’s pilgrimage at very close quarters. I had this access both as a bishop and as a commentator for NBC News. It was thrilling indeed to witness just how rapturously the American people received the pope and how affected the Holy Father was by this reception. Many images stay vividly in my mind: the pope kissing the forehead of the 10-year-old boy with cerebral palsy, the rabbi and imam praying together at the September 11 memorial, a little boy from a New York Catholic school showing the pope how to maneuver his way around a Smart Board. But what stays most powerfully with me is the pope speaking to a joint meeting of the United States Congress in Washington, D.C.

My first assignment for NBC was the Today Show’s coverage of the pope’s arrival on the south lawn of the White House. As I sat on the platform with Matt Lauer and Maria Shriver, I looked across at the stately obelisk of the Washington Monument, and I remembered an extraordinary event from the mid- nineteenth century. Along with many other world leaders, Pope Pius IX had sent a block for the construction of the monument to the father of our country, but an angry mob of anti-Catholic bigots took that piece of marble and threw it into the Potomac. This, of course, was not an isolated or purely egregious act of vandalism; rather, it partook of a widespread and deeply-rooted hatred of Catholicism that lasted in this country in fairly virulent form up to the election of John F. Kennedy in 1960. That the Pope of Rome would be graciously received at the White House and welcomed to speak before the entire Congress of the United States would have struck most Americans, for much of our history, as simply unthinkable. And this is why (and I’ll confess it openly) my eyes filled with tears as I saw the pope standing at the rostrum in the House of Representatives, the cheers of the gathered lawmakers washing over him.

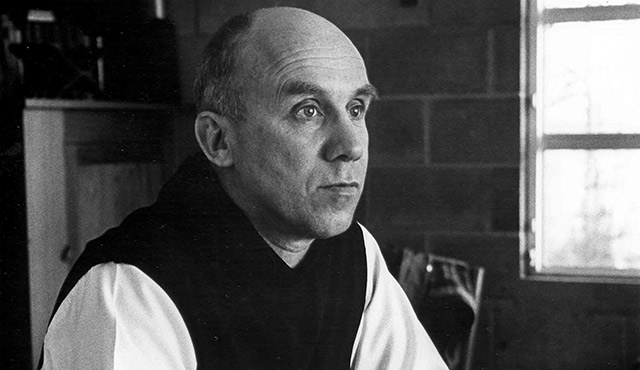

And as I listened to the pope’s words that day, I was even more astonished. As is his wont, Francis didn’t trade in abstractions. Instead, he focused his remarks on four outstanding figures from American history–Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr., Dorothy Day, and Thomas Merton–each of whom spoke of some dimension of authentic freedom. Anyone familiar with my work over the years would know that all four of these people are heroes of mine. I have a photo of Lincoln over the desk in my office; I have written extensively on King and have done a number of videos on his life and legacy; Dorothy Day is featured prominently in my documentary “Catholicism”; and Thomas Merton is, quite simply, one of the major reasons that I entered the priesthood, and a photo of him is in eyeshot as I type these words.

I would love to explore the pope’s analysis of each of these giants, but given the limited scope of this article, I will focus on the one I consider the most important, namely Merton. What Merton signaled for the pope was the openness to dialogue with other religions to be sure, but also and more significantly, the contemplative openness to the reality of God, to a dimension that goes beyond the empirical world and the achievements of the individual ego. This is of supreme importance, for when a sense of God evanesces–as it has increasingly in our secularized Western world–all we have left for understanding human affairs are psychological and political categories. Armed only with these, we fall into the customary patterns of left and right, liberal and conservative, open to change and suspicious of change, etc. And this, furthermore, makes Catholic social teaching so confounding to the pundits and politicos. How can the Catholic Church simultaneously advocate against abortion and assisted suicide but for immigration reform and attention to the poor? How can it stand against the abuse of the environment and for the free market, against the death penalty, and for the family? With God out of the picture, it is indeed hard to make sense of such an array of opinions, but with God at the heart of things, the various positions of the Church fall into harmony, much like the medallions in a rose window. If God exists, then every individual person that he has created is a subject of rights, freedom, and dignity. If God exists, then no one is expendable and everyone is equally worthy of respect. It is none other than the contemplative attitude exemplified by Thomas Merton that reveals this deep consistency.

How wonderful and strange that a pope would be addressing Congress at all, but how surpassing wonderful and strange it was that he should use the occasion to hold up before the lawmakers of the most powerful nation on earth the example of a Trappist monk who gave his life to the contemplation of God.

Bishop Robert Barron is an auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and the founder of Word on Fire Catholic Ministries.